Barton Receives Simons Foundation Early Career Award

Oceanographer to study the diversity of phytoplankton off La Jolla

June 9, 2017

By Mallory Pickett

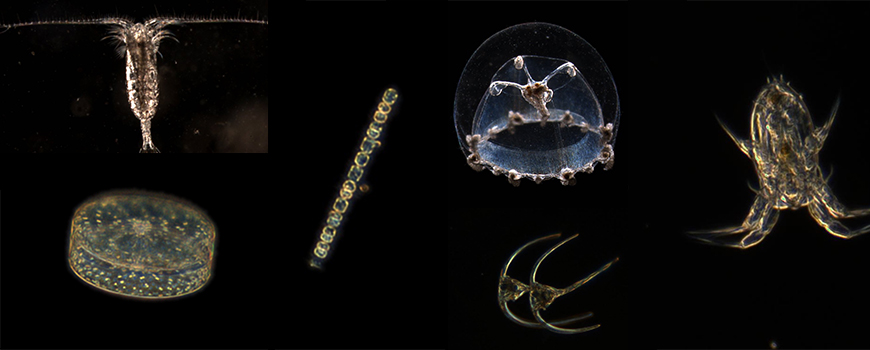

Marine phytoplankton are famously photogenic.

Andrew Barton

Take, for instance, diatoms. They are among the most common type of phytoplankton and are especially breathtaking: their cell walls are made of silica, a glass-like compound, and take a variety of forms including discs, tubes, and star-like structures.

Scientists have long sought to understand the factors that contribute to the diversity of phytoplankton.

"Presumably all these different shapes have some ecological meaning," said Andrew Barton, an assistant professor at the University of California San Diego's Division of Biological Sciences and Scripps Institution of Oceanography. "Some shapes might be hard to eat, or maybe are advantageous for acquiring scarce resources."

Barton has just received the Simons Foundation Early Career Investigation in Marine Microbial Ecology and Evolution Award, which will support an interdisciplinary research project to attempt to answer this question.

The project will use a combination of underwater microscope data from the Scripps Pier Plankton Camera operated by the Jaffe Laboratory for Underwater Imaging, environmental data from the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System (SCCOOS), and numerical models that simulate plankton communities to understand the ecological reasons for the poorly understood diversity in phytoplankton shapes and sizes.

The Scripps Plankton Camera is an underwater microscope deployed at the Scripps Pier that uses real-time image processing and object detection to monitor plankton species and abundance. Barton and his team will combine data collected by the microscope and the SCCOOS environmental data to look for correlations between environmental conditions and abundance of different kinds of plankton over time. The information they gather will help researchers understand the local environment better. Barton and his team will also create numerical models to extrapolate the trends they see to the rest of the ocean.

"We can take what we learn from the data at Scripps Pier and try to extrapolate that to a larger-scale perspective", Barton said. "For example, where in the global ocean is it advantageous to be a spherical cell? Where is it advantageous to form large colonies of cells? We can try to make some estimates of how cell and colony morphology vary across the planet".

The outcomes of the project could also help answer oceanographic questions beyond phytoplankton ecology. Phytoplankton are an important part of the carbon cycle and their contributions to carbon dioxide uptake from the atmosphere and oxygen creation is a significant factor in most oceanographic and climate models.

"Most models and theories about how phytoplankton do what they do are predicated on them being spheres, which is obviously untrue," Barton said.

The size and shape of organisms in the ocean is important in determining where carbon and energy go in the food web, and whether the carbon absorbed will be exported from the ocean's surface to the deep sea or sediments. Providing updated information on phytoplankton morphology and how it varies throughout the world's oceans could improve science's understanding of the carbon cycle.

Various plankton in ocean waters off La Jolla, Calif.

Jaffe Research Group at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego

For example, "if you have a really dense large cell like a diatom, it will sink from the ocean's surface, resulting in a loss of organic matter," Barton said, "whereas if you have a small cell, it may just stay near the surface and be recycled locally."

The interdisciplinary research will involve Jules Jaffe, a research oceanographer in the Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps, Paul Roberts, an engineer in Jaffe's lab and Peter Franks, a professor of biological oceanography who will help the team estimate water column turbulence and understand how turbulence in the ocean shapes cell and colony morphology.

"I'm really grateful for the Simons Foundation support and happy that we now have the team and the tools to do some compelling and important science," Barton said.

And as Barton is a relatively new faculty member, this big project will be an excellent opportunity for him to collaborate with other researchers at Scripps.

"This is kind of a kick-off in terms of collaborating with a Scripps team and using data collected here at the institution," he said. "I'm very excited."